The use of a perpetual inventory system for merchandise provides the most effective means of control over this important asset. Although it is impossible to maintain a perpetual inventory in memorandum records only or to limit the data to quantities, a complete set of records integrated with the general ledger is preferable. The basic feature of the system is the recording of all merchandise increases and decreases in a manner somewhat similar to the recording of increases and decreases in cash. Just as receipts of cash are debited to Cash so are purchases of merchandise debited to Merchandise Inventory. Similarly, sales or other reductions of merchandise are recorded in a manner comparable to that employed for reductions in Cash, that is, by credits to Merchandise Inventory. Thus, just as the balance of the cash account indicates the amount of cash presumed to be on hand, so the balance of the merchandise inventory account represents the amount of merchandise presumed to be on hand.

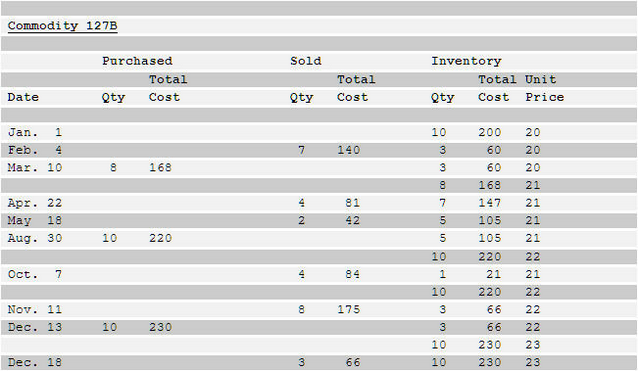

Unlike cash, merchandise is a heterogeneous mass of commodities. Details of the cost of each type of merchandise purchased and sold, together with such related transactions as returns and allowances, must be maintained in a subsidiary ledger, with a separate account for each type. Thus an enterprise that stocks five hundred types of merchandise would need five hundred individual accounts in its inventory ledger. The flow of costs through a subsidiary account is illustrated below. There was a beginning inventory, three purchases, and six sales of the particular commodity during the year covered. The number of units on hand after each transaction, together with total cost and unit prices appears in the inventory section of the account.

[Tab.1o]

With a perpetual system, as in a periodic system of inventory determination, it is necessary to identify the item sold with a specific group or to employ a cost flow assumption. In the foregoing illustration the first-in, first-out flow method of costing was used. Note that after the 7 units of the commodity were sold on February 4 there was a remaining inventory of 3 units at $20 each. The 8 units purchased on March 10 were acquired at a unit cost of $21, instead of $20, and hence could not be combined with the 3 units. The inventory after the March 10 purchase is therefore reported on two lines, 3 units at $20 each and 8 units at $21 each. Next, it should be noted that the $81 cost of the 4 units sold on April 22 is composed of the remaining 3 units at $20 each and 1 unit at $21. Finally, the 10 units of the commodity in the inventory at the end of the period is composed of the last units acquired, which were purchased at $23 each.

When the last-in, first-out flow method of costing is strictly applied to a perpetual inventory system, the unit cost prices assigned to the ending inventory will not necessarily be those associated with the earliest unit costs of the period. The unit costs for the ending inventory will vary from those obtained by use of the periodic costing system if at any time the number of units of a commodity sold exceeds the number previously purchased during the same period. This situation is not unusual, and when it occurs, the excess quantity sold is deducted from the opening inventory balance. An example of such a temporary reduction of the inventory appears in the perpetual inventory account illustrated above. The cost of the 7 units of the commodity sold on February 4 reduced the opening inventory to 3 units priced at $20 each. They were replaced on March 10 but at a unit price of $21 instead of $20.

Application of the last-in, first-out method to the data in the illustration, using the periodic inventory system, would yield an ending inventory of 10 units at $20, which corresponds to the opening inventory. Re-determination of balances in the illustrative perpetual inventory account, however, yields a last-in, first-out inventory composed of 3 units at $20 each and 7 units at $23 each. This is an obvious departure from the underlying purpose of the lifo costing method, which is to deduct the current cost of merchandise from current sales revenue. One method of avoiding pricing problems of this type is to maintain the perpetual inventory accounts throughout the period in terms of quantities only, inserting the cost data at the end of the period. Another variation in procedure is to record both quantities and costs in the subsidiary accounts during the period, thus providing data needed for interim statements; any required adjustments are then made to price the inventory at the end of the year at the earliest costs and to apply the most recent costs against the year's sales revenue.

The weighted average method of cost flow can be applied to the perpetual system, though in a somewhat modified form. Instead of determining a weighted average price for each type of commodity at the end of a period, an average unit price is computed each time a purchase is made. The unit price so computed is then used to determine the cost of the items sold until another purchase is made. This averaging technique is called a moving average.

In the periodic system discussed previously, sales of merchandise were recorded by debits to the cash or accounts receivable account and credits to the sales account. The cost of the merchandise sold was not determined for each sale. It was determined only periodically by means of a physical inventory. In contrast to the periodic system, the perpetual system provides the cost data related to each sale. The cost data for sales on account may be accumulated in a special column inserted in the sales journal. Each time merchandise is sold on account the amount entered in the "cost" column represents a debit to Cost of Merchandise Sold and a credit to Merchandise Inventory. Similar provisions can be made for cash sales.

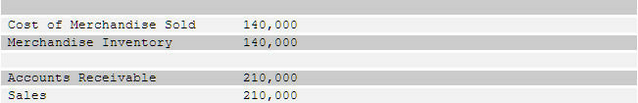

To illustrate sales on account under the perpetual inventory system, assume that the monthly total of the cost column of the sales journal is $140,000 and that the monthly total of the sales column is $210,000. The effect on the general ledger accounts is indicated by the two entries below, in general journal form.

[Tab.1p]

The control feature is the most important advantage of the perpetual system. The inventory of each class of merchandise is always readily available in the subsidiary ledger. A physical count of any class of merchandise can be made at any time and compared with the balance of the subsidiary account to determine the existence and seriousness of any shortages. When a shortage is discovered, an entry is made debiting Inventory Shortages and crediting Merchandise Inventory for the cost. If the balance of the inventory shortages account at the end of a fiscal period is relatively minor, it may be included in miscellaneous general expense on the income statement. Otherwise it may be separately reported in the general expense section.

In addition to the usefulness of the perpetual inventory system in the preparation of interim statements, the subsidiary ledger can be an aid in maintaining inventory quantities at an optimum level. Frequent comparisons of quantity balances with predetermined maximum and minimum levels facilitate both (1) the timely reordering of merchandise to avoid the loss of sales and (2) the avoidance of excessive accumulation of inventory.